Commenting in code

Writing comments in code is commonly discouraged and considered a code smell (including in Robert C. Martin’s Clean Code, which I highly recommend). The reason for this is that comments are not as visually perceivable as the actual code, especially with most editors’ colour schemes. This leads to comments not being updated when the code is updated, and becoming misleading or even incorrect over time.

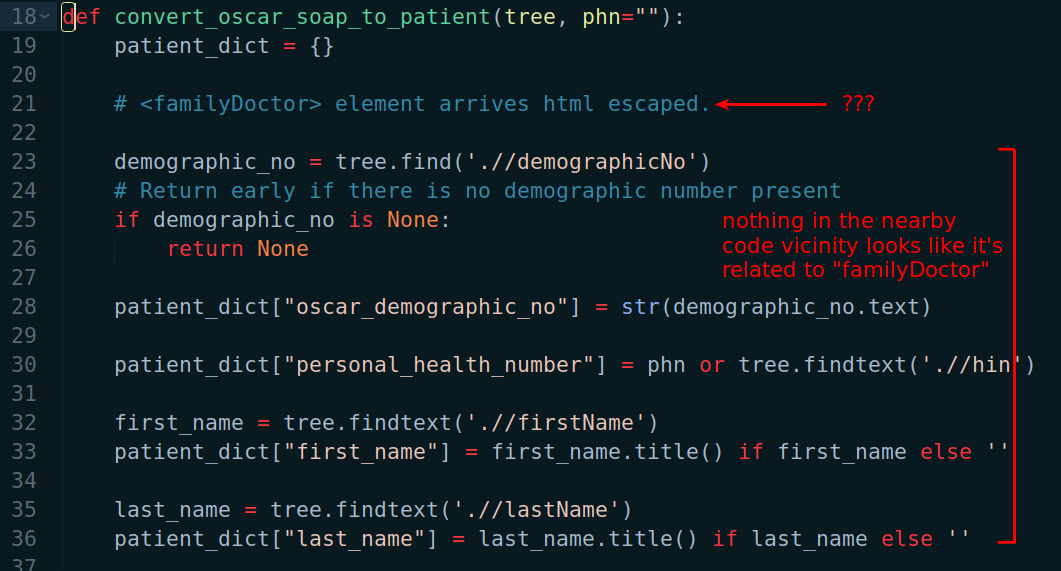

Here’s an example where (I think?) the comment is referring to code that has been removed or refactored:

Sometimes comments may be helpful in explaining logic that may not be intuitive or clear. This is a slightly better example of commenting (because it explains the reasoning for this logic).

def patient_lookup_view(request):

...

# Terminals behave differently from online booking regarding patient statuses.

# Terminals block any patient that isn't 'AC' (Active) and displays a message

# asking the patient to talk to an MOA.

if patient_dict and patient_dict['patient_status'] != 'AC':

messages.warning(request, ERROR_INACTIVE_PATIENT)

return redirect('/patients')

...

However, this still has the risk of devs forgetting to update the comment if the intended behaviour of the app changes in the future, and then this comment would be confusing and incorrect. It’s up to the developer’s judgment when these kinds of comments are beneficial and worth writing.

What Martin encourages instead is naming your variables and functions so that the intention of the code is more clear.

In the following example, it’s difficult to understand what behaviour is intended by if within_hrs(appointment.start_date_time, 8) and location in [LOCATION_PHONE, LOCATION_VIDEO], which is why the explanatory comment is needed.

def send_confirmation_email(...):

...

bcc = []

# See if doctor should be BCC (same day remote appointments)

doctor = appointment.get_doctor()

if within_hrs(appointment.start_date_time, 8) and location in [LOCATION_PHONE, LOCATION_VIDEO]:

if doctor.user and doctor.user.email:

bcc.append(doctor.user.email)

...

We could improve the readability of this code first by abstracting this logic into a helper function, should_bcc_doctor().

Aside: another principle discussed in Clean Code is reducing the scope of your functions (“Single responsibility principle”). This way, your function should avoid having to do many things, or having to know about both general and specific information. In this example, the function does the general thing of sending a confirmation email, but it also has to know about really specific details of whether it’s a same day remote appointment in order to bcc the doctor. These specific details should be moved to helper functions.

Next, we could break down the logic in if within_hrs(appointment.start_date_time, 8) and location in [LOCATION_PHONE, LOCATION_VIDEO] into smaller pieces: is_same_day and is_remote_appointment. Checking for if is_same_day and is_remote_appointment should (hopefully!) be easier to skim and understand.

def send_confirmation_email(...):

...

bcc = []

if should_bcc_doctor(appointment, location, doctor):

bcc.append(doctor.user.email)

...

def should_bcc_doctor(appointment, location, doctor):

if not (doctor.user and doctor.user.email):

return False

is_same_day = within_hrs(appointment.start_date_time, 8)

is_remote_appointment = location in [LOCATION_PHONE, LOCATION_VIDEO]

if is_same_day and is_remote_appointment:

return True

return False

Another aside: I forget where I read this but someone recommended naming booleans with is_ (is_same_day vs same_day) because it’s clear from the name alone that is_same_day is a boolean.